Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, readers will demonstrate proficiency in large-sample econometric analysis using Python by:

5.1 Implementing consistency checks for OLS estimators through Monte Carlo simulation using NumPy random number generation.

5.2 Computing large-sample test statistics and confidence intervals using asymptotic normal distributions via scipy.stats.

5.3 Applying heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors (HC0, HC1, HC2, HC3) using statsmodels cov_type parameter.

5.4 Conducting large-sample hypothesis tests with F-statistics and Chi-square distributions for joint restrictions.

5.5 Evaluating asymptotic efficiency of estimators through simulation studies comparing variance properties across sample sizes.

5.6 Implementing the Lagrange multiplier (LM) test as an alternative to Wald and likelihood ratio tests using statsmodels.

Asymptotic theory provides the foundation for statistical inference when sample sizes are large, describing the limiting behavior of OLS estimators as . This chapter establishes consistency and asymptotic normality of OLS estimators, develops large-sample inference procedures, and addresses practical complications including heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors and asymptotically efficient estimation methods.

The presentation builds from fundamental concepts to practical applications. We begin by establishing consistency and asymptotic normality under the Gauss-Markov assumptions (Section 5.1), demonstrate large-sample hypothesis testing and confidence interval construction (Section 5.2), examine asymptotic efficiency through the Gauss-Markov theorem’s large-sample analog (Section 5.3), and conclude with robust inference methods when assumptions fail (Section 5.4). Throughout, we emphasize the practical relevance of asymptotic approximations for finite samples typically encountered in applied econometric research.

Asymptotic Properties of OLS¶

Under the Gauss-Markov assumptions MLR.1-MLR.4 (from Chapter 3: linearity, random sampling, no perfect collinearity, and zero conditional mean), OLS estimators have the following asymptotic properties:

1. Consistency: as for all

The OLS estimators converge in probability to the true parameter values as the sample size grows large. Consistency is a weaker property than unbiasedness--it only requires that the estimator approaches the true value asymptotically. Notably, consistency does not require normality (MLR.6) or homoscedasticity (MLR.5).

2. Asymptotic Normality: as

By the Central Limit Theorem (CLT), the sampling distribution of approaches a normal distribution as , even when the errors are not normally distributed. This requires:

MLR.1-MLR.4 (especially zero conditional mean)

Finite fourth moments of the errors: (mild regularity condition)

No normality assumption required

Practical Implications:

With large samples ( typically), t-tests and F-tests are approximately valid even without normal errors (MLR.6)

Consistency means OLS remains reliable in large samples even under violations of MLR.5 (heteroskedasticity)

Asymptotic inference requires only MLR.1-MLR.4 plus regularity conditions, making it more robust than finite-sample inference

We will use simulations to visualize these concepts and then apply the Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test to a real-world example.

Connection to Previous Chapters:

Chapters 2-3 established finite-sample properties under Gauss-Markov assumptions

Chapter 4 showed exact inference requires normality (MLR.6) for finite samples

This chapter demonstrates that normality is not necessary for large-sample inference

These results justify the robustness claims made in Chapter 4 about t-tests with

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

import wooldridge as woo

from scipy import stats

# Configure matplotlib to avoid font parsing issues

plt.rcParams['mathtext.fontset'] = 'dejavusans'5.1 Consistency of OLS¶

Consistency is a fundamental asymptotic property that describes whether an estimator converges to the true parameter value as the sample size grows infinitely large. While unbiasedness (Chapter 3) is a finite-sample property, consistency is a large-sample property.

5.1.1 Definition and Importance¶

Definition: An estimator of parameter is consistent if:

This means: For any , as .

In words: As the sample size increases, the probability that the estimator is far from the true value approaches zero.

Why Consistency Matters:

Asymptotic reliability: With large enough samples, consistent estimators give us values close to the truth

Weaker than unbiasedness: An estimator can be biased but still consistent (bias vanishes as )

Minimum requirement: Consistency is the least we should expect from an estimator

Practical relevance: Most real-world datasets are large enough for asymptotics to apply

Example: Sample Mean

Consider estimating the population mean using the sample mean .

By the Law of Large Numbers (LLN):

The sample mean is consistent for the population mean under weak conditions (just need and finite variance).

5.1.2 Consistency of OLS Estimators¶

Theorem (Consistency of OLS): Under assumptions MLR.1-MLR.4:

MLR.1: Linear in parameters

MLR.2: Random sampling

MLR.3: No perfect collinearity

MLR.4: Zero conditional mean ()

The OLS estimators are consistent:

Key Observations:

No normality required (MLR.6): We don’t need normal errors for consistency

No homoscedasticity required (MLR.5): Heteroscedasticity doesn’t affect consistency

Zero conditional mean is crucial (MLR.4): Omitted variable bias prevents consistency

Practical Implication: Even if errors are heteroskedastic or non-normal, OLS estimates converge to true values with large samples.

5.1.3 When Consistency Fails: Omitted Variable Bias¶

The zero conditional mean assumption (MLR.4) is critical for consistency. If it fails due to omitted variables, OLS is inconsistent.

Example: Wage Equation with Omitted Ability

True model:

Estimated model (ability unobserved):

where .

If , then:

This violates MLR.4, so is inconsistent even as !

# Demonstrate consistency vs inconsistency with simulation

np.random.seed(42)

# Simulation parameters

sample_sizes = [50, 100, 500, 1000, 5000, 10000]

n_replications = 1000

# True parameters

beta_0 = 1.0

beta_1_educ = 0.08 # True return to education

beta_2_ability = 0.5 # True effect of ability

# Storage for results

results_consistent = []

results_inconsistent = []

for n in sample_sizes:

# Generate data for all replications

ability = stats.norm.rvs(0, 1, size=(n_replications, n))

educ = 12 + 2 * ability + stats.norm.rvs(0, 2, size=(n_replications, n)) # Ability affects education

u = stats.norm.rvs(0, 0.5, size=(n_replications, n))

log_wage = beta_0 + beta_1_educ * educ + beta_2_ability * ability + u

# Consistent estimator: Include ability (correct model)

X_correct = np.stack([np.column_stack((np.ones(n), educ[i], ability[i])) for i in range(n_replications)])

XtX = X_correct.transpose(0, 2, 1) @ X_correct

XtX_inv = np.linalg.inv(XtX)

y_expanded = log_wage[:, :, np.newaxis]

beta_correct = (XtX_inv @ X_correct.transpose(0, 2, 1) @ y_expanded)[:, 1, 0]

# Inconsistent estimator: Omit ability (misspecified model)

X_omit = np.stack([np.column_stack((np.ones(n), educ[i])) for i in range(n_replications)])

XtX_omit = X_omit.transpose(0, 2, 1) @ X_omit

XtX_inv_omit = np.linalg.inv(XtX_omit)

beta_omit = (XtX_inv_omit @ X_omit.transpose(0, 2, 1) @ y_expanded)[:, 1, 0]

results_consistent.append({

'n': n,

'mean': np.mean(beta_correct),

'std': np.std(beta_correct),

'bias': np.mean(beta_correct) - beta_1_educ

})

results_inconsistent.append({

'n': n,

'mean': np.mean(beta_omit),

'std': np.std(beta_omit),

'bias': np.mean(beta_omit) - beta_1_educ

})

# Create comparison table

comparison_df = pd.DataFrame({

'Sample Size': sample_sizes,

'Consistent (With Ability)': [f"{r['mean']:.4f}" for r in results_consistent],

'Bias (Consistent)': [f"{r['bias']:.4f}" for r in results_consistent],

'Inconsistent (Omit Ability)': [f"{r['mean']:.4f}" for r in results_inconsistent],

'Bias (Inconsistent)': [f"{r['bias']:.4f}" for r in results_inconsistent],

})

display(comparison_df)Interpretation:

Consistent estimator (includes ability): Bias approaches zero as increases

Inconsistent estimator (omits ability): Bias persists even with n=10,000

This demonstrates that no amount of data can fix omitted variable bias

The Consistency Lesson

Key Takeaway: Consistency requires correct model specification (MLR.4).

Consistency is NOT guaranteed by:

Large sample size alone

Sophisticated statistical techniques

High R-squared

Consistency IS guaranteed by:

Including all relevant variables (no omitted variable bias)

Valid instrumental variables (Chapter 15)

Correct functional form

Random assignment (experiments)

5.2 Asymptotic Normality and Large Sample Inference¶

While consistency tells us that OLS converges to the true value, asymptotic normality describes the distribution of the OLS estimator in large samples. This is crucial for hypothesis testing and confidence intervals.

5.2.1 The Central Limit Theorem (CLT)¶

The Central Limit Theorem is one of the most important results in statistics. In the context of OLS:

Theorem (Asymptotic Normality of OLS): Under MLR.1-MLR.5:

Or equivalently:

where is the j-th diagonal element of and .

What This Means:

As , the t-statistic follows a standard normal distribution

We can use the normal distribution to construct confidence intervals and test hypotheses

This holds even if errors are not normally distributed (huge advantage!)

5.2.2 Why Normality Assumption is “Too Strong”¶

In Chapter 4, we assumed MLR.6: Normality () for exact finite-sample inference. But:

Problems with Normality Assumption:

Rarely true in practice: Economic variables often have skewed or heavy-tailed distributions

Restrictive: Rules out many plausible error distributions

Unnecessary for large samples: CLT provides normality asymptotically

Not testable in a useful way: We observe , not

Examples Where Normality Fails:

Income/wage data: Typically right-skewed (log-normal or Pareto distributions)

Count data: Number of arrests, patent applications (Poisson-like distributions)

Binary outcomes: 0/1 variables cannot be normally distributed

Financial returns: Fat tails, excess kurtosis (not normal)

5.2.3 Large Sample Inference Without Normality¶

Key Result: For (rule of thumb), we can use:

t-tests:

Confidence Intervals:

Unexpected end of input in a macro argument, expected '}' at end of input: …text{ (95% CI)}

\hat{\beta}_j \pm 1.96 \cdot \text{se}(\hat{\beta}_j) \text{ (95% CI)}F-tests:

Advantages of Asymptotic Inference:

Robustness: Works with non-normal errors

Simplicity: Use standard normal critical values instead of t-distribution

Flexibility: Applies to heteroskedastic errors (with robust SEs)

Wide applicability: Most econometric methods rely on asymptotics

Finite vs Asymptotic Inference

Finite Sample (Exact) Inference:

Requires MLR.1-MLR.6 (including normality)

Use t-distribution with degrees of freedom

Exact for any sample size

Rarely satisfied in practice

Asymptotic (Large Sample) Inference:

Requires only MLR.1-MLR.4 (no normality or homoskedasticity)

Use standard normal distribution

Approximate for large (typically )

Much more realistic in applications

Practical Recommendation: Use asymptotic inference with robust standard errors (Chapter 8) for most applications.

5.3 Asymptotic Efficiency of OLS¶

Efficiency concerns whether an estimator has the smallest possible variance among all consistent estimators. OLS has strong efficiency properties under certain conditions.

5.3.1 The Gauss-Markov Theorem (Revisited)¶

Recall from Chapter 3: Under MLR.1-MLR.5, OLS is BLUE (Best Linear Unbiased Estimator) in finite samples.

Asymptotic Version: Under MLR.1-MLR.5, OLS is asymptotically efficient among linear estimators:

where Avar denotes asymptotic variance.

5.3.2 When is OLS Inefficient?¶

OLS can be inefficient (not best) when:

Heteroskedasticity (MLR.5 fails):

OLS is still consistent but no longer BLUE

Weighted Least Squares (WLS) is more efficient

Use robust standard errors for valid inference (Chapter 8)

Serial correlation (time series, Chapter 12):

OLS standard errors are incorrect

Need heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors

Endogeneity (MLR.4 fails):

OLS is inconsistent

Use Instrumental Variables (IV) or 2SLS (Chapter 15)

IV is consistent but less efficient than OLS when OLS is valid

Practical Implication: If MLR.1-MLR.5 hold, you can’t systematically beat OLS in terms of efficiency. But if MLR.5 fails, there are more efficient estimators (though OLS remains consistent).

5.3.3 Trade-off: Efficiency vs Robustness¶

# Simulate efficiency comparison: OLS vs WLS under heteroskedasticity

np.random.seed(123)

n = 500

n_replications = 1000

# True parameters

beta_0 = 2.0

beta_1 = 0.5

# Generate data with heteroskedasticity: Var(u|x) = x^2

x = stats.uniform.rvs(1, 10, size=(n_replications, n)) # x between 1 and 11

u = x * stats.norm.rvs(0, 1, size=(n_replications, n)) # Var(u|x) = x^2

y = beta_0 + beta_1 * x + u

# OLS estimation (ignores heteroskedasticity)

X_ols = np.stack([np.column_stack((np.ones(n), x[i])) for i in range(n_replications)])

XtX = X_ols.transpose(0, 2, 1) @ X_ols

XtX_inv = np.linalg.inv(XtX)

y_expanded = y[:, :, np.newaxis]

beta_ols = (XtX_inv @ X_ols.transpose(0, 2, 1) @ y_expanded)[:, 1, 0]

# WLS estimation (accounts for heteroskedasticity)

# Weights: w_i = 1 / x_i^2 (optimal under Var(u|x) = x^2)

weights = 1 / x**2

W = np.array([np.diag(weights[i]) for i in range(n_replications)])

X_wls = X_ols

XtWX = X_wls.transpose(0, 2, 1) @ W @ X_wls

XtWX_inv = np.linalg.inv(XtWX)

y_weighted = (W @ y_expanded)

beta_wls = (XtWX_inv @ X_wls.transpose(0, 2, 1) @ y_weighted)[:, 1, 0]

# Compare efficiency

efficiency_comparison = pd.DataFrame({

'Estimator': ['OLS (Inefficient)', 'WLS (Efficient)', 'Efficiency Gain'],

'Mean Estimate': [

np.mean(beta_ols),

np.mean(beta_wls),

'-'

],

'Standard Deviation': [

np.std(beta_ols),

np.std(beta_wls),

f"{(np.std(beta_ols) / np.std(beta_wls) - 1) * 100:.1f}%"

],

'Interpretation': [

'Consistent but not efficient',

'Consistent and efficient',

'WLS has lower variance'

]

})

display(efficiency_comparison)Interpretation:

Both OLS and WLS are consistent (converge to 0.5)

WLS has lower standard deviation (more efficient)

Under heteroskedasticity, WLS can be substantially more efficient

5.4 Testing Normality of the Error Term¶

Given the importance (or lack thereof) of the normality assumption, you might wonder: Should we test whether errors are normally distributed?

5.4.1 Why Testing Normality is “Not Actionable”¶

The Dilemma: Suppose we test and:

Reject normality: What do we do?

Can’t “fix” non-normal errors

OLS is still consistent (MLR.1-MLR.4)

Use asymptotic inference (which doesn’t require normality anyway)

Fail to reject normality: What do we conclude?

Lack of evidence against normality evidence for normality

With small samples, test has low power

With large samples, we don’t need normality anyway (CLT)

The Bottom Line: Testing normality doesn’t lead to an actionable response in most cases.

5.4.2 Common Normality Tests¶

Despite the above, normality tests are sometimes reported:

1. Jarque-Bera Test:

where = skewness, = kurtosis of residuals.

2. Shapiro-Wilk Test: Based on correlation between residuals and expected order statistics

3. Anderson-Darling Test: Weighted version of Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

Example: Jarque-Bera Test

# Perform Jarque-Bera test on wage equation residuals

wage1 = woo.data('wage1')

reg = smf.ols('np.log(wage) ~ educ + exper + tenure', data=wage1).fit()

# Get residuals

residuals = reg.resid

# Jarque-Bera test

from statsmodels.stats.stattools import jarque_bera

jb_stat, jb_pval, skew, kurtosis = jarque_bera(residuals)

normality_test = pd.DataFrame({

'Test': ['Jarque-Bera'],

'Statistic': [f'{jb_stat:.3f}'],

'p-value': [f'{jb_pval:.4f}'],

'Skewness': [f'{skew:.3f}'],

'Kurtosis': [f'{kurtosis:.3f}'],

'Conclusion': ['Reject normality' if jb_pval < 0.05 else 'Fail to reject normality']

})

display(normality_test)5.4.3 Practical Recommendations¶

What to do instead of testing normality:

Check for influential observations:

Look for outliers that might distort results

Use robust regression methods if needed

Examine residual plots:

Plot residuals vs fitted values

Look for patterns suggesting misspecification

Use robust inference:

Always use heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors (Chapter 8)

They’re valid under both homoskedasticity and heteroskedasticity

Check functional form:

Test for nonlinearities (Chapter 6)

Use RESET test for misspecification

Consider transformation:

Log transformation often reduces skewness

Can improve linearity and homoskedasticity simultaneously

Don’t Obsess Over Normality

Key Message: Normality of errors is:

NOT required for consistency (only need MLR.1-MLR.4)

NOT required for large-sample inference (CLT provides asymptotic normality)

NOT required for efficiency (only need homoskedasticity)

NOT testable in a useful way (residuals ≠ errors)

Do worry about:

Omitted variables (destroys consistency)

Heteroskedasticity (use robust SEs)

Influential observations (check diagnostics)

Functional form misspecification (test with RESET)

Focus your energy on specification and identification, not on normality testing!

5.5 Simulation Exercises¶

In this section, we will conduct simulation exercises to illustrate the asymptotic properties of the OLS estimator, particularly focusing on its distribution as the sample size increases under different scenarios.

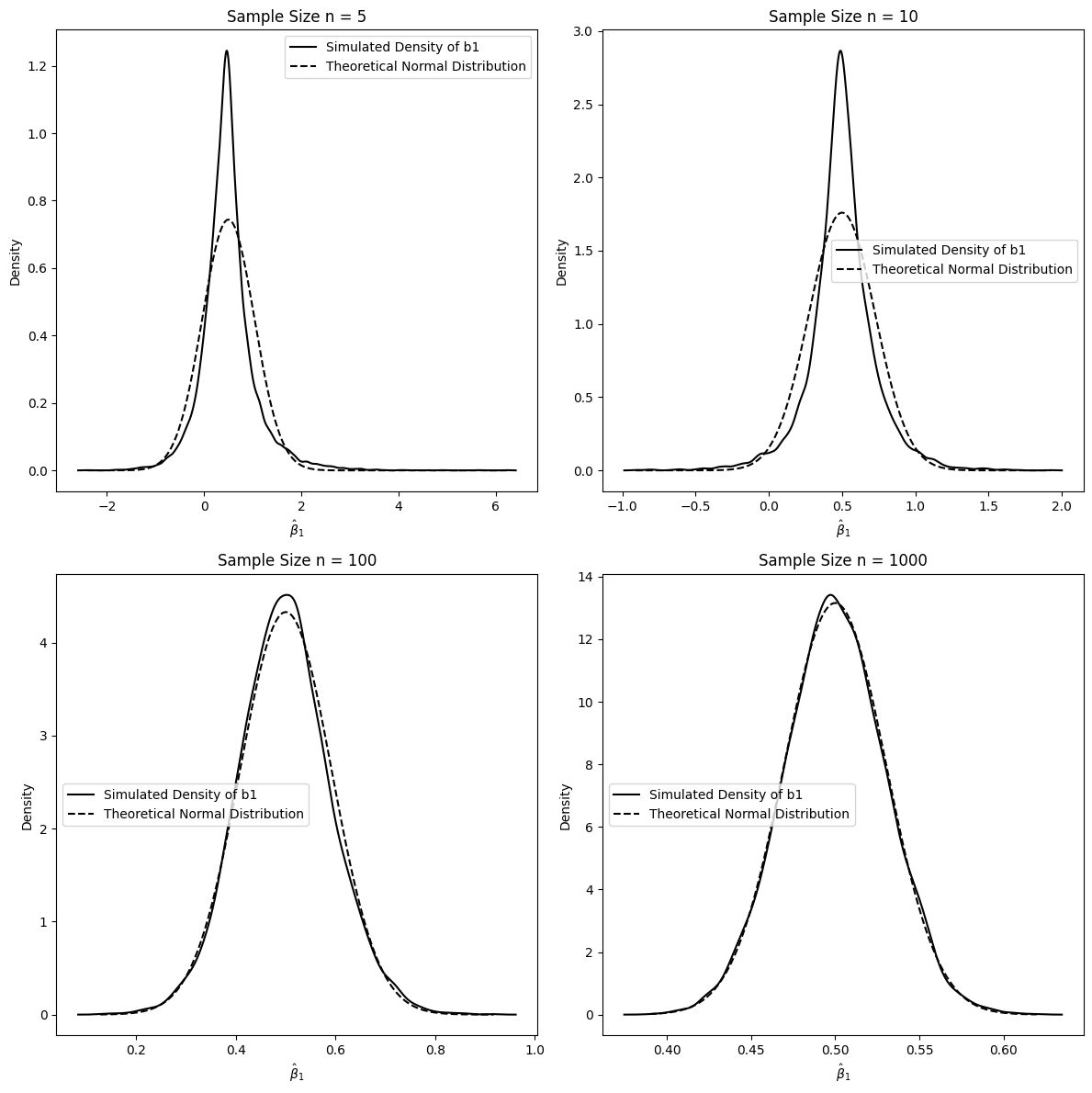

5.1.1 Normally Distributed Error Terms¶

This simulation demonstrates the behavior of the OLS estimator when the error terms are normally distributed. Under the classical linear model assumptions, including normally distributed errors, the OLS estimators are not only BLUE (Best Linear Unbiased Estimator) but also have desirable properties even in small samples. Asymptotically, the OLS estimator is consistent and normally distributed. We will visualize how the distribution of the estimated coefficient approaches a normal distribution as the sample size increases.

# Monte Carlo Simulation Setup: OLS with Normal Errors

# Demonstrates convergence to normality as sample size increases

# Set random seed for reproducible results

np.random.seed(1234567)

# Configure simulation parameters

sample_sizes = [5, 10, 100, 1000] # n: Small to large samples

num_replications = 10000 # r: Number of Monte Carlo iterations

# Define true population parameters (Data Generating Process)

# True model: y = beta_0 + beta_1x + u, where u ~ N(0, 1)

true_intercept = 1.0 # beta_0 = 1

true_slope = 0.5 # beta_1 = 0.5

x_std_dev = 1.0 # sigma_x: Standard deviation of x

x_mean = 4.0 # mu_x: Mean of x

# SIMULATION 1: OLS WITH NORMAL ERRORS

sim_info = pd.DataFrame(

{

"Parameter": [

"Data Generating Process",

"X Distribution",

"Error Distribution",

"Replications",

],

"Value": [

f"y = {true_intercept} + {true_slope}*x + u",

f"X ~ N({x_mean}, {x_std_dev}^2)",

"u ~ N(0, 1)",

f"{num_replications:,}",

],

},

)

display(sim_info)

# Create visualization grid for results

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(12, 12))

axes = axes.ravel() # Flatten for easier iteration

# Run simulation for each sample size

for idx, n in enumerate(sample_sizes):

# Step 1: Generate fixed x values for this sample size

# X is held constant across replications to isolate error term effects

x_values = stats.norm.rvs(x_mean, x_std_dev, size=n)

# Step 2: Generate error terms for all replications

# Shape: (num_replications, n) - each row is one replication

error_terms = stats.norm.rvs(0, 1, size=(num_replications, n))

# Step 3: Generate y values using true DGP

# y = beta_0 + beta_1*x + u for each replication

y_values = true_intercept + true_slope * x_values + error_terms

# Step 4: Construct design matrix X (same for all replications)

# X = [1, x] where first column is for intercept

X_matrix = np.column_stack((np.ones(n), x_values))

# Step 5: Pre-compute matrix operations for efficiency

# (X'X)^(-1)X' is constant across replications since X is fixed

XtX_inv = np.linalg.inv(X_matrix.T @ X_matrix)

XtX_inv_Xt = XtX_inv @ X_matrix.T

# Step 6: Estimate coefficients for all replications at once

# beta_hat = (X'X)^(-1)X'y for each replication

# Result: 2 x num_replications matrix (each column = one replication)

all_coefficients = XtX_inv_Xt @ y_values.T

slope_estimates = all_coefficients[1, :] # Extract beta_hat_1 (second row)

# Step 7: Calculate theoretical standard error for comparison

# Under CLM assumptions: Var(beta_hat) = sigma^2(X'X)^(-1), where sigma^2 = 1

variance_matrix = XtX_inv # Since sigma^2 = 1

theoretical_se = np.sqrt(variance_matrix[1, 1]) # SE(beta_hat_1)

# Step 8: Estimate empirical density using kernel density estimation

kde = sm.nonparametric.KDEUnivariate(slope_estimates)

kde.fit()

# Step 9: Generate theoretical normal distribution for comparison

x_range = np.linspace(min(slope_estimates), max(slope_estimates), 1000)

theoretical_density = stats.norm.pdf(x_range, true_slope, theoretical_se)

# Step 10: Plot empirical vs theoretical distributions

axes[idx].plot(

kde.support,

kde.density,

color="black",

linewidth=2,

label="Empirical Density (KDE)",

)

axes[idx].plot(

x_range,

theoretical_density,

linestyle="--",

color="red",

linewidth=1.5,

label="Theoretical Normal",

)

# Add visualization details

axes[idx].set_ylabel("Density")

axes[idx].set_xlabel(r"$\hat{\beta}_1$ (Slope Estimate)")

axes[idx].legend(loc="best", fontsize=9)

axes[idx].set_title(f"Sample Size n = {n}")

axes[idx].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Add statistics annotation

mean_est = np.mean(slope_estimates)

std_est = np.std(slope_estimates)

axes[idx].text(

0.05,

0.95,

f"Mean: {mean_est:.4f}\nStd: {std_est:.4f}",

transform=axes[idx].transAxes,

verticalalignment="top",

fontsize=8,

bbox=dict(boxstyle="round", facecolor="wheat", alpha=0.5),

)

plt.suptitle("Convergence to Normality: OLS with Normal Errors", fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show() # Display the plotInterpretation of 5.1.1:

The plots above show the simulated density of the OLS estimator for different sample sizes () when the error term is normally distributed. We compare this simulated density to the theoretical normal distribution that should asymptotically follow.

Small Sample Sizes (n=5, 10): For very small sample sizes, the simulated density of is somewhat close to the normal distribution, but there are noticeable deviations. This is because while OLS is BLUE under these conditions, the asymptotic normality is approached as .

Larger Sample Sizes (n=100, 1000): As the sample size increases to and , the simulated density of gets increasingly closer to the theoretical normal distribution. For , the simulated density is almost indistinguishable from the normal distribution.

This simulation visually confirms that when the errors are normally distributed, the distribution of the OLS estimator approaches a normal distribution as the sample size increases, consistent with asymptotic theory and even showing reasonable approximation for smaller sample sizes in this ideal scenario.

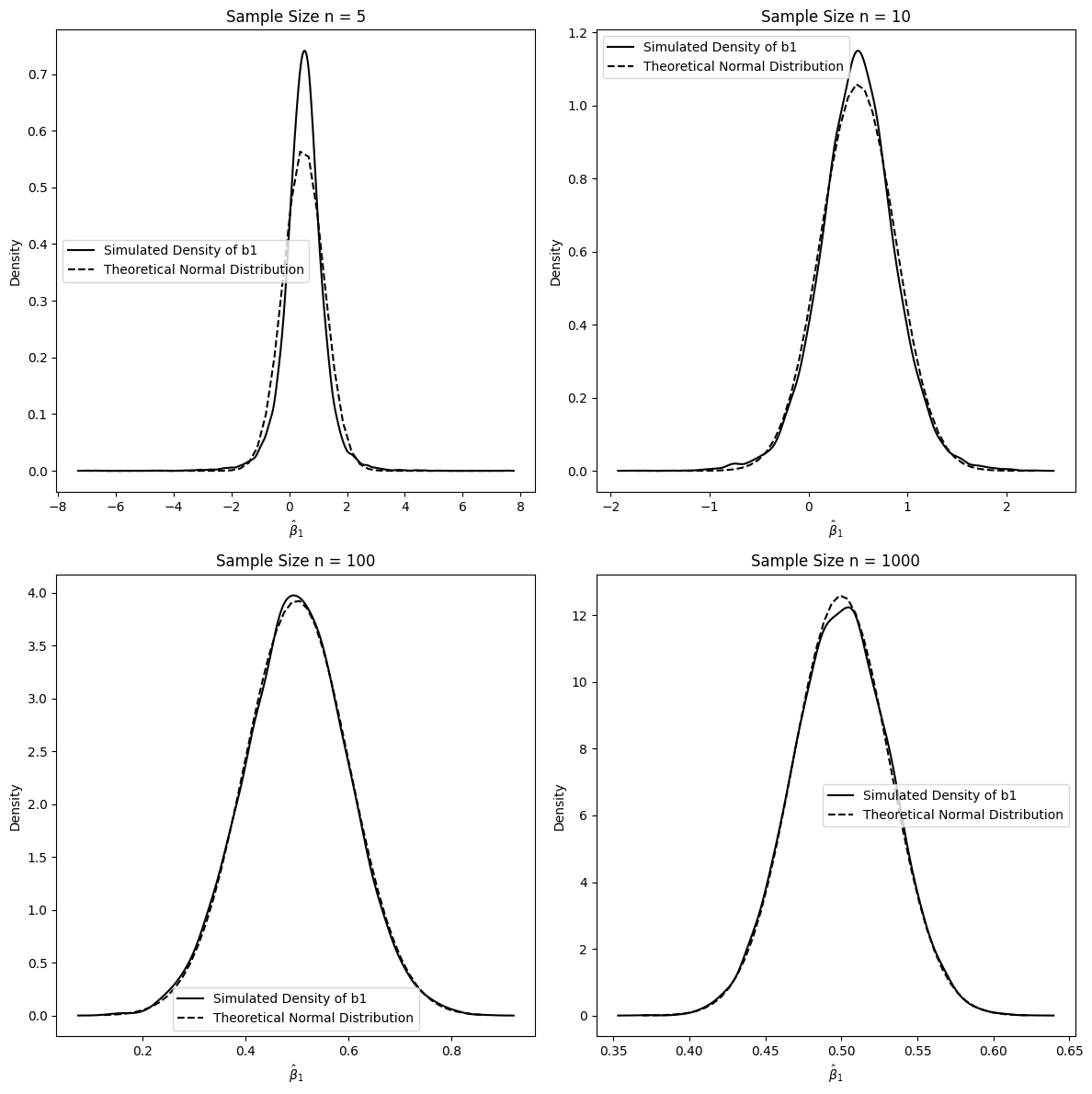

5.1.2 Non-Normal Error Terms¶

In this simulation, we investigate what happens when one of the classical linear model assumptions is violated - specifically, the assumption of normally distributed errors. We will use error terms that follow a standardized Chi-squared distribution with 1 degree of freedom. Even when the error term is not normally distributed, under the Gauss-Markov conditions and assuming homoskedasticity and no autocorrelation, OLS is still BLUE. More importantly, even with non-normal errors, the OLS estimator is still consistent and asymptotically normally distributed under weaker conditions (CLT for sample averages). This simulation will demonstrate the asymptotic normality even with non-normal errors.

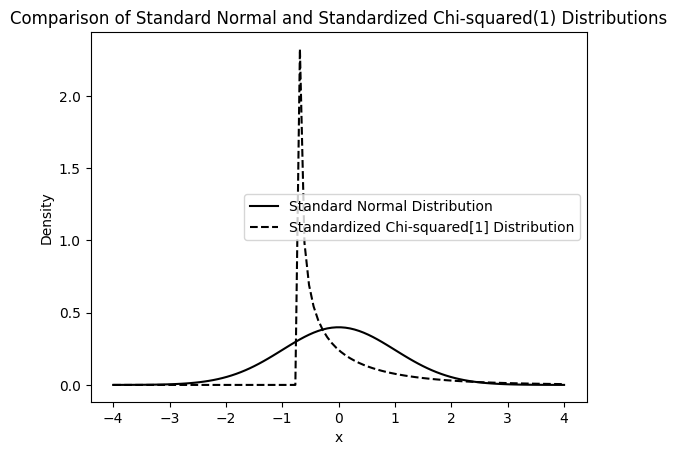

First, let’s visualize the shape of the standardized Chi-squared distribution compared to the standard normal distribution.

# support of normal density:

x_range = np.linspace(-4, 4, num=100)

# pdf for standard normal distribution:

pdf_n = stats.norm.pdf(x_range)

# pdf for standardized chi-squared distribution with 1 degree of freedom.

# We subtract the mean (which is 1 for chi2(1)) and divide by the standard deviation (which is sqrt(2) for chi2(1)) to standardize it.

pdf_c = stats.chi2.pdf(x_range * np.sqrt(2) + 1, 1)

# plot:

plt.plot(

x_range,

pdf_n,

linestyle="-",

color="black",

label="Standard Normal Distribution",

)

plt.plot(

x_range,

pdf_c,

linestyle="--",

color="black",

label="Standardized Chi-squared[1] Distribution",

)

plt.xlabel("x")

plt.ylabel("Density")

plt.legend()

plt.title("Comparison of Standard Normal and Standardized Chi-squared(1) Distributions")

plt.show()

The plot above shows that the standardized Chi-squared distribution is skewed to the right and has a different shape compared to the standard normal distribution. Now, let’s perform the simulation with these non-normal errors.

# set the random seed for reproducibility:

np.random.seed(1234567)

# set sample sizes to be investigated:

n = [5, 10, 100, 1000]

# set number of simulations (replications):

r = 10000

# set true population parameters:

beta0 = 1 # true intercept

beta1 = 0.5 # true slope coefficient

sx = 1 # standard deviation of x

ex = 4 # expected value of x

# Create a 2x2 subplot to display density plots for each sample size

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(12, 12))

axs = axs.ravel() # Flatten the 2x2 array of axes for easier indexing

# Loop through each sample size in the list 'n'

for idx, j in enumerate(n):

# draw a sample of x, fixed over replications:

x = stats.norm.rvs(ex, sx, size=j)

# Create the design matrix X. For each replication, X is the same as 'x' is fixed.

X = np.column_stack((np.ones(j), x))

# Compute (X'X)^(-1)X' once as X is fixed for each n.

XX_inv = np.linalg.inv(X.T @ X)

XTX_inv_XT = XX_inv @ X.T

# Generate error terms 'u' from a standardized Chi-squared distribution with 1 degree of freedom for all replications at once.

u = (stats.chi2.rvs(1, size=(r, j)) - 1) / np.sqrt(2)

# Compute the dependent variable 'y' for all replications at once using the true model: y = beta0 + beta1*x + u

y = beta0 + beta1 * x + u

# Estimate beta (including beta0 and beta1) for all 'r' replications at once.

b = XTX_inv_XT @ y.T

b1 = b[1, :] # Extract all estimated beta1 coefficients.

# Estimate the PDF of the simulated b1 estimates using Kernel Density Estimation (KDE).

kde = sm.nonparametric.KDEUnivariate(b1)

kde.fit()

# Theoretical normal density, calculated the same way as in the normal error case.

Vbhat = XX_inv # Variance-covariance matrix

se = np.sqrt(np.diagonal(Vbhat))

x_range = np.linspace(min(b1), max(b1), 1000)

y = stats.norm.pdf(x_range, beta1, se[1])

# plotting:

axs[idx].plot(

kde.support,

kde.density,

color="black",

label="Simulated Density of b1",

)

axs[idx].plot(

x_range,

y,

linestyle="--",

color="black",

label="Theoretical Normal Distribution",

)

axs[idx].set_ylabel("Density")

axs[idx].set_xlabel(r"$\hat{\beta}_1$")

axs[idx].legend()

axs[idx].set_title(f"Sample Size n = {j}")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Interpretation of 5.1.2:

These plots illustrate the distribution of when the error terms are from a standardized Chi-squared distribution, which is non-normal.

Small Sample Sizes (n=5, 10): For small sample sizes, the simulated density of is noticeably skewed and deviates from the normal distribution, reflecting the non-normality of the error term.

Larger Sample Sizes (n=100, 1000): As the sample size increases, the simulated density of becomes progressively more symmetric and approaches the theoretical normal distribution. By , the simulated distribution is very close to normal, even though the underlying errors are non-normal.

This simulation demonstrates the power of the Central Limit Theorem in action. Even when the errors are not normally distributed, the OLS estimator , which is a function of the sample average of the error terms (indirectly), becomes approximately normally distributed as the sample size grows large. This is a key result in asymptotic theory, justifying the use of normal distribution based inference (t-tests, confidence intervals) in OLS regression with large samples, even if we suspect the errors are not normally distributed.

5.1.3 (Not) Conditioning on the Regressors¶

In previous simulations (5.1.1 and 5.1.2), we fixed the regressors across replications for each sample size . This is akin to conditioning on the regressors. In econometric theory, we often derive properties of OLS estimators conditional on the observed values of the regressors. However, in reality, regressors are also random variables. This simulation explores the implications of not conditioning on the regressors by drawing new samples of in each replication, along with new error terms. We will see if the asymptotic normality of still holds when both and are randomly drawn in each simulation run.

# set the random seed for reproducibility:

np.random.seed(1234567)

# set sample sizes to be investigated:

n = [5, 10, 100, 1000]

# set number of simulations (replications):

r = 10000

# set true population parameters:

beta0 = 1 # true intercept

beta1 = 0.5 # true slope coefficient

sx = 1 # standard deviation of x

ex = 4 # expected value of x

# Create a 2x2 subplot to display density plots for each sample size

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(12, 12))

axs = axs.ravel() # Flatten the 2x2 array of axes for easier indexing

# Loop through each sample size in the list 'n'

for idx, j in enumerate(n):

# Draw samples of x and u, varying over replications

# Shape: (r replications, j observations)

x = stats.norm.rvs(ex, sx, size=(r, j))

u = stats.norm.rvs(0, 1, size=(r, j))

y = beta0 + beta1 * x + u

# Vectorized OLS estimation across all replications

# Create design matrices for all replications: shape (r, j, 2)

X_all = np.stack([np.column_stack((np.ones(j), x[i])) for i in range(r)], axis=0)

# Compute (X'X)^(-1) for all replications using vectorized operations

# X_all.transpose(0, 2, 1) has shape (r, 2, j)

# @ X_all gives (r, 2, 2) - all X'X matrices

XtX = X_all.transpose(0, 2, 1) @ X_all # Shape: (r, 2, 2)

XtX_inv = np.linalg.inv(XtX) # Vectorized inverse: Shape (r, 2, 2)

# Compute (X'X)^(-1)X' for all replications: Shape (r, 2, j)

XtX_inv_Xt = XtX_inv @ X_all.transpose(0, 2, 1)

# Estimate beta for all replications: Shape (r, 2, 1)

# Expand y to shape (r, j, 1) for matrix multiplication

y_expanded = y[:, :, np.newaxis]

b = XtX_inv_Xt @ y_expanded # Shape: (r, 2, 1)

b1 = b[:, 1, 0] # Extract all slope coefficients (beta_1)

# Simulated density using KDE

kde = sm.nonparametric.KDEUnivariate(b1)

kde.fit()

# Theoretical normal density

# Average (X'X)^(-1) over replications for theoretical variance

avg_XX_inv = np.mean(XtX_inv, axis=0)

Vbhat = sx * avg_XX_inv # Variance-covariance matrix

se = np.sqrt(np.diagonal(Vbhat))

x_range = np.linspace(min(b1), max(b1))

y = stats.norm.pdf(x_range, beta1, se[1])

# plotting:

axs[idx].plot(

kde.support,

kde.density,

color="black",

label="Simulated Density of b1",

)

axs[idx].plot(

x_range,

y,

linestyle="--",

color="black",

label="Theoretical Normal Distribution",

)

axs[idx].set_ylabel("Density")

axs[idx].set_xlabel(r"$\hat{\beta}_1$")

axs[idx].legend()

axs[idx].set_title(f"Sample Size n = {j}")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Interpretation of 5.1.3:

In this simulation, both the regressors and the error terms are randomly drawn in each replication.

Small Sample Sizes (n=5, 10): Similar to the previous simulations, with very small sample sizes, the simulated distribution of shows some deviation from the normal distribution.

Larger Sample Sizes (n=100, 1000): As the sample size increases, even when we are not conditioning on the regressors, the distribution of still converges to a normal distribution. By , the convergence is quite evident.

This simulation reinforces the asymptotic normality of the OLS estimator even when we consider the randomness of the regressors. The key conditions for asymptotic normality are related to the properties of the population and the law of large numbers and central limit theorem applying to sample averages, which hold true whether we condition on regressors or not, as long as certain regularity conditions are met (like finite variance of and , and exogeneity). This is fundamental because in most econometric applications, regressors are indeed random variables.

5.6 The Lagrange Multiplier (LM) Test¶

The Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test, also called the score test, is an asymptotic test used to test restrictions on parameters in regression models. In econometrics, it is commonly used to test for omitted variables or other forms of model misspecification.

Key Advantage: The LM test only requires estimation of the restricted model (under the null hypothesis), making it computationally attractive when the unrestricted model is complex.

Asymptotic Equivalence: Under standard regularity conditions, the LM test, Wald test, and Likelihood Ratio (LR) test are asymptotically equivalent - they have the same limiting distribution under . In practice with large samples, they often give similar conclusions.

For testing restrictions in a linear regression model, the LM test statistic is often computationally simpler than the Wald or F tests, especially when the null hypothesis involves multiple restrictions on coefficients.

For testing restrictions of the form in a linear regression, where is a matrix and is a vector, the LM test statistic can be calculated as:

where:

is the sample size.

is the R-squared from a regression of the residuals from the restricted model () on all the independent variables in the unrestricted model.

is the number of restrictions being tested (degrees of freedom).

denotes a Chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom.

The steps to perform an LM test are typically as follows:

Estimate the Restricted Model: Estimate the regression model under the null hypothesis. Obtain the residuals from this restricted model ().

Auxiliary Regression: Regress the residuals from the restricted model on all the independent variables from the unrestricted model. Calculate the from this auxiliary regression ().

Calculate the LM Statistic: Compute the LM test statistic as .

Determine the p-value: Compare the LM statistic to a distribution, where is the number of restrictions. Calculate the p-value or compare the LM statistic to a critical value from the distribution to make a decision.

Example 5.3: Economic Model of Crime¶

We will use the crime1 dataset from the wooldridge package to illustrate the LM test. The example considers an economic model of crime where the number of arrests (narr86) is modeled as a function of several factors.

The unrestricted model is:

We want to test the null hypothesis that avgsen (average sentence length) and tottime (total time served) have no effect on narr86, i.e., . Thus, we have restrictions.

The restricted model under is:

crime1 = woo.dataWoo("crime1")

# 1. Estimate the restricted model under H0: beta_avgsen = 0 and beta_tottime = 0

reg_r = smf.ols(formula="narr86 ~ pcnv + ptime86 + qemp86", data=crime1)

fit_r = reg_r.fit()

r2_r = fit_r.rsquared

# Display R-squared of Restricted Model

pd.DataFrame(

{

"Model": ["Restricted"],

"R-squared": [f"{r2_r:.4f}"],

},

)# 2. Obtain residuals from the restricted model and add them to the DataFrame

crime1["utilde"] = fit_r.resid

# 3. Run auxiliary regression: regress residuals (utilde) on ALL variables from the UNRESTRICTED model

reg_LM = smf.ols(

formula="utilde ~ pcnv + ptime86 + qemp86 + avgsen + tottime",

data=crime1,

)

fit_LM = reg_LM.fit()

r2_LM = fit_LM.rsquared

# Display R-squared of LM Regression

pd.DataFrame(

{

"Model": ["LM Auxiliary"],

"R-squared": [f"{r2_LM:.4f}"],

},

)# 4. Calculate the LM test statistic: LM = n * R^2_utilde

LM = r2_LM * fit_LM.nobs

# Display LM Test Statistic

pd.DataFrame(

{

"Statistic": ["LM Test"],

"Value": [f"{LM:.3f}"],

},

)# 5. Determine the critical value from the chi-squared distribution with q=2 degrees of freedom at alpha=10% significance level

# For a test at 10% significance level, alpha = 0.10.

# We want to find the chi-squared value such that the area to the right is 0.10.

cv = stats.chi2.ppf(1 - 0.10, 2) # ppf is the percent point function (inverse of CDF)

# Display Critical Value

pd.DataFrame(

{

"Test": ["Chi-squared critical value"],

"df": [2],

"Alpha": [0.10],

"Value": [f"{cv:.3f}"],

},

)# 6. Calculate the p-value for the LM test

# The p-value is the probability of observing a test statistic as extreme as, or more extreme than, the one calculated, under the null hypothesis.

pval = 1 - stats.chi2.cdf(LM, 2) # cdf is the cumulative distribution function

# Display P-value for LM Test

pd.DataFrame(

{

"Test": ["LM Test"],

"p-value": [f"{pval:.4f}"],

},

)# 7. Compare the LM test to the F-test for the same hypothesis using the unrestricted model directly.

reg = smf.ols(

formula="narr86 ~ pcnv + avgsen + tottime + ptime86 + qemp86",

data=crime1,

)

results = reg.fit()

# Define the hypotheses to be tested: beta_avgsen = 0 and beta_tottime = 0

hypotheses = ["avgsen = 0", "tottime = 0"]

# Perform the F-test

ftest = results.f_test(hypotheses)

fstat = ftest.statistic

fpval = ftest.pvalue

# Display F-test results

pd.DataFrame(

{

"Statistic": ["F-statistic", "p-value"],

"Value": [f"{fstat:.3f}", f"{fpval:.4f}"],

},

)Interpretation of Example 5.3:

LM Test Statistic: The calculated LM test statistic is 4.071.

Critical Value: The critical value from the distribution at the 10% significance level is 4.605.

P-value: The p-value for the LM test is 0.1306.

Since the LM test statistic (4.071) is less than the critical value (4.605), or equivalently, the p-value (0.1306) is greater than the significance level (0.10), we fail to reject the null hypothesis . This suggests that avgsen and tottime are jointly statistically insignificant in explaining narr86, given the other variables in the model.

Comparison with F-test: The F-test directly tests the same hypothesis using the unrestricted model. The F-statistic is 2.034 and the p-value is 0.1310.

The results from the LM test and the F-test are very similar in this case, leading to the same conclusion: we fail to reject the null hypothesis. In linear regression models, under homoskedasticity, the LM test, Wald test, and F-test are asymptotically equivalent for testing linear restrictions on the coefficients. In practice, especially with reasonably large samples, these tests often provide similar conclusions. The LM test is advantageous when estimating the unrestricted model is more complex or computationally intensive, as it only requires estimating the restricted model.

Chapter Summary¶

This chapter explored the asymptotic properties of OLS estimators, demonstrating that large-sample inference is more robust and widely applicable than the finite-sample methods covered in Chapter 4. Asymptotic theory allows us to make valid inferences even when classical assumptions like normality fail.

Key Concepts:

1. Consistency: OLS estimators converge in probability to true parameter values as under minimal assumptions (MLR.1-MLR.4). Consistency requires correct specification (no omitted variable bias) but NOT normality or homoskedasticity. It’s the minimum we should expect from an estimator.

2. Asymptotic Normality: By the Central Limit Theorem, follows an approximate normal distribution in large samples, even when errors are NOT normally distributed. This powerful result allows us to use t-tests, confidence intervals, and F-tests with non-normal data, provided the sample is large enough (typically ).

3. Asymptotic Efficiency: Under the Gauss-Markov assumptions (MLR.1-MLR.5), OLS is asymptotically efficient among linear estimators. When heteroskedasticity is present (MLR.5 fails), OLS remains consistent but loses efficiency to Weighted Least Squares (WLS). However, we can still use OLS with robust standard errors for valid inference.

4. Normality Testing is Not Actionable: Testing whether errors are normally distributed rarely leads to useful actions. If we reject normality, we should rely on asymptotic inference anyway (which doesn’t require normality). If we fail to reject, it doesn’t confirm normality. Focus instead on specification, outliers, and using robust inference.

5. The Lagrange Multiplier (LM) Test: An asymptotic alternative to F-tests and Wald tests for testing parameter restrictions. The LM test only requires estimating the restricted model, making it computationally attractive. Under standard conditions, LM, Wald, and Likelihood Ratio tests are asymptotically equivalent.

Practical Implications:

For Inference:

With , use asymptotic inference (standard normal critical values)

Always use heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors (Chapter 8) as default

Don’t worry about normality of errors - worry about specification

LM tests are useful when unrestricted models are complex

For Consistency:

Correct specification is crucial - no amount of data fixes omitted variable bias

Consistency requires MLR.4 (zero conditional mean):

Include all relevant variables or use instrumental variables (Chapter 15)

Check for functional form misspecification (Chapter 6)

For Efficiency:

OLS is efficient under homoskedasticity (MLR.5)

Under heteroskedasticity, consider WLS or GLS for improved efficiency

But OLS + robust SEs is a reasonable default strategy

Don’t sacrifice consistency for efficiency

Simulation Insights:

Our simulations demonstrated three key asymptotic results:

Normal errors (Section 5.5.1): Even with normal errors, small samples deviate from asymptotic theory. Convergence to normality is clear by .

Non-normal errors (Section 5.5.2): With chi-square errors (highly skewed), OLS estimates still converge to normality by , confirming the CLT’s power.

Random regressors (Section 5.5.3): Asymptotic normality holds whether we condition on regressors or treat them as random, reflecting real-world applications where is random.

Comparison with Finite-Sample Theory (Chapter 4):

| Property | Finite Sample (Ch 4) | Asymptotic (Ch 5) |

|---|---|---|

| Unbiasedness | Requires MLR.1-MLR.4 | Not needed (only consistency) |

| Normality | Requires MLR.6 for exact inference | NOT required (CLT provides asymptotic normality) |

| Homoskedasticity | Needed for BLUE | Not needed for consistency; use robust SEs |

| Inference | Exact with t and F distributions | Approximate with standard normal and |

| Sample Size | Any | Large (typically ) |

| Robustness | Sensitive to violations | More robust to assumption violations |

Looking Forward:

Chapter 6 explores functional form, scaling, and model selection - all crucial for correct specification

Chapter 8 covers heteroskedasticity in detail, including robust standard errors and efficiency considerations

Chapter 15 introduces instrumental variables for handling endogeneity when MLR.4 fails

The Bottom Line:

Asymptotic theory is the workhorse of modern econometrics. It allows us to:

Make valid inferences with non-normal, heteroskedastic data

Justify the use of OLS in a wide variety of settings

Understand when and why OLS might fail (inconsistency from omitted variables)

Develop alternative estimators and tests (LM, GMM, IV)

Most importantly: Focus on getting the specification right (avoiding omitted variable bias, choosing correct functional form) rather than obsessing over classical assumptions like normality. With correct specification and large samples, OLS with robust standard errors is a reliable, general-purpose tool for empirical analysis.